Hügelkultur - Sheetmulching Raised to New Heights

In my last Permaculture post I discussed mulching as an effective way to help the water retention of your soil, while providing lots of nutrients over an extended time. Today I want to keep raising this technique to new levels, quite literally, in the form of Hügelkultur. Hügel means Hill in German (and I bet you can guess Kultur!), so this gardening method is often called hill or mound beds in English. Essentially they are advanced forms of lasagna beds, which also includes thick logs and other large-scale organic debris, and can rise up to shoulder high above ground level.

Multiple Benefits of a Hügel Bed

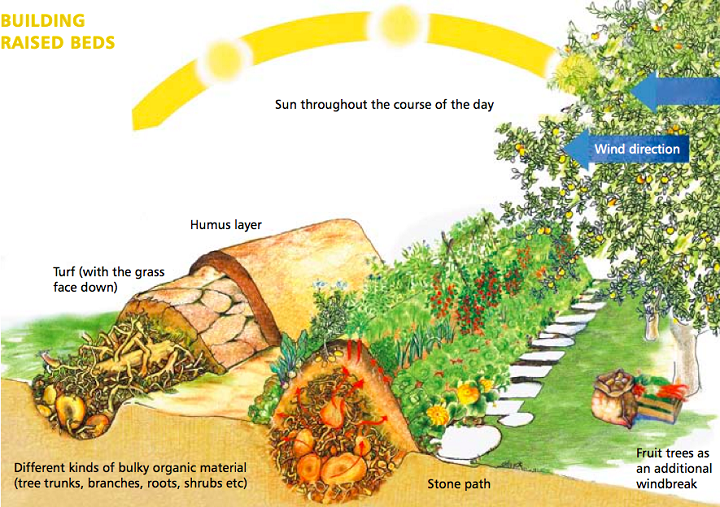

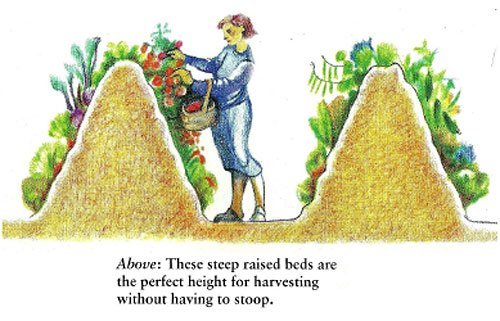

Just as in the case of sheetmulching, the ground is covered with various layers of compostable materials. Unlike with simple sheetmulching, the logs and branches inside a Hügel will take several years to decompose, offering your plants many seasons of nutrients. Since the bulk of the mound is made up of wood, the decomposing material will become more and more porous, which can soak up more and more water. Due to the constant decomposition inside the bed, and the elevated planting area above the level of ground frost, the Hügel is also likely to extend your growing season. This is especially true if you build it in a horseshoe form, opening towards the South, creating an effective suntrap. The elevated planting beds also come in handy for gardening work you don't have to bend down for.

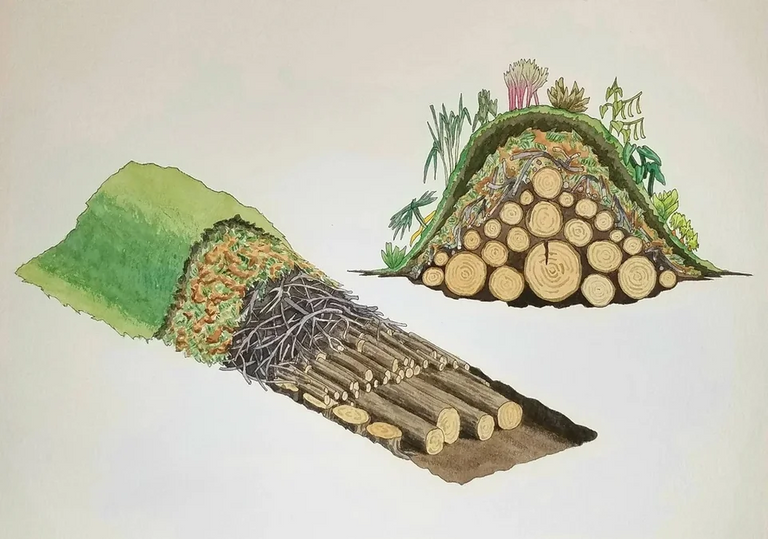

Building Your Hügel-culture

A Hügelkulture can be built from the ground up, or you may dig a trench underneath if you're counting on plenty of water. The rule of thumb is always to put the material that takes the longest to decompose on the bottom, and build your way up from there. Recently cut logs, heartwood, or hardwood go way down below, followed by wood that is already rotting away happily. On top of the thicker logs you place layers of thinner branches, twigs, wood chips, then continue with straw, leaves, compost, and finally a good layer of fertile soil that you can plant into right away. Around the leaves and straw you may also include a layer of manure, cardboard, lawn clippings, kitchen compost, or whatever organic wastes you may have lying around. Just make sure they are well covered. And don't forget to water each layer to give your Hügel a good head start.

Is All The Extra Work Really Worth It?

Granted, compared to a regular lasagna bed, a Hügelkultur involves a lot more work: Logs, branches, and sticks need to be cut and moved into place, then covered in several layers, which due to its hill shape will require a lot more material, while at the same time the benefits of a Hügel are pretty much the same as in sheetmulching: water retention and long term release of nutrients. Still, I would say the difference between the two is immense, since the Hügel does all that much better, and over longer time periods. So if you have the material available - and what else would you be doing with so much rotting wood? - I would say it's definitely worth the effort.

Note: I wrote this post and published it on this external site a few months ago. You can find more sustainability related posts in my series Permaculture in Theory and Practice.

Another favorite method that I tried last year

!ENGAGE

Nice! So I assume it's still up and feeding your plants you planted in it.

Will see this year. I made 3 small beds in autumn and have some onions in one, others keep them for tomatoes :)

tökjo, epitettel mar ilyent?

Igen, ezt itt Kanadában csináltuk egy pár éve:

👍

cool to still see you around! :)

Thank you, and likewise!

This is indeed useful, worth patience and a bit more material investment. No doubts results are great and can last for years until all mulch goodies disappear.

For sure! The pic in the reply below is of a Hügel I helped some friends build in Canada five years ago. From what I hear, it's still going.

Hello @stortebeker !

Very interesting and instructive. Thank you. Now another question - where did you find the umlaut ü on your keyboard?😂

@missagora

Hahaha, it's not that easy, since it's not included in the original keyboard. So I got two different keyboard layouts, the regular English US and the alternative English US intl. with dead keys. In that one everything is included, even the long ű and ő we use in Hungarian, plus a bunch of other stuff I never use. It only takes a click to switch from one to the other... But also I should have mentioned that my operating system is Linux Mint. Not sure if Microsoft systems have the same options too.

We also use Linux. I have a German keyboard on my computer because I speak German and my husband has the US keyboard.

Hi! We recently saw the documentary Back to Eden, and were very convinced about the mulching as we were planning to do that to the garden now. However this is also intriguing and we have many logs on the property that we would need to hash to mulch with a machine, but now this method would not demand such extra machinery.. In your experience, would you think the Hügelkultur is a better option? What intrigues me is that there is no "soil", do the roots go all through the logs into the soil, or is the system counting on the organic matter and wood to turn into compost soil eventually?

Blessings!

I definitely think it's a better option than grinding everything down. However, regarding the soil, it is always a combination of factors, so I would not forego the machine entirely.

Take the Hügel I helped build in Canada (there is a pic in one of these comment replies). We used pretty big logs, but that was not all. Since we had a chipper at hand, we also added a layer of wood chips, along with leaves, straw, manure, and actual soil. Sure in comparison the soil and the manure were of modest quantities, but they are important to help to get the decomposition process going.

The roots will always find their ways, at first around the logs. As things start to decompose, it is first the leaves and the straw that turns into soil. Later the wood chips and the thinner branches. But eventually it's the logs' turn, and yes: Just as you guessed, the roots will make use of those holes and crevices created inside the decomposing logs to reach the nutrients that are being liberated in the process. (To be more exact, before the roots, it is the fungus mycelia around those roots that find their way into the logs, but that's the next step down the rabbit-hole of composting...)