Explained: Could Erdogan win the next presidential election? (No)

On May the 14th, Turkey is due to go to the polls to elect a new parliament and president. At time of writing, incumbent President Erdogan is well behind in the polls, and his government's cack handed response to the recent earthquake has put him under even more pressure. Nonetheless, however unlikely Erdogan's re-election might seem, it would be foolish to write off a politician who has won basically every election in Turkey for the past 20 years or so. So in this article, we're going to take a look at three reasons why Erdogan might actually win the next election. The fact that the main opposition candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, just isn't a good candidate. The so-called Kurdish question and Erdogan and the AKP's control over Turkish political institutions.

Let's get into the first reason Erdogan might actually win the election Kemal Kilicdaroglu. Basically, the main opposition parties in Turkey have realized that if they want to beat Erdogan, they need to work as a coalition. And last week they finally agreed on a presidential candidate, Kemal Kilicdaroglu. In some sense, Kilicdaroglu was the obvious choice. He's the leader of the largest opposition party, the Republican People's Party, which was created by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the first president and founder of the modern Turkish Republic. He's also been in politics longer than the other candidates, and he's a good diplomat who's widely credited for building and holding together an ideologically diverse coalition of opposition parties, hence his nickname as Turkish Gandhi.

However, whatever his merits, he's relatively unpopular, and his record at the ballot box against Erdogan is, well, not great. Since taking over in 2010, Kilicdaroglu has been on the losing side to Erdogan at four parliamentary elections, two presidential elections and two referendums. In the past, Erdogan has mocked him as a serial loser and there were calls for his resignation after the 2018 election. While polling from around the time of the earthquake gives him a 14 point lead. Polling in Turkey is notoriously unreliable, and Erdogan has held a slight lead over him before the earthquake. Perhaps more importantly, though, Kilicdaroglu is significantly less popular than the other opposition candidates. Metropol Polling from late last year, for example, put him neck and neck with Erdogan, but gave Mansur Yavas and Ekrem Imamoglu Kilicdaroglu's proposed vice presidents a 17 and nine point lead respectively.

Yavas and Imamoglu are the opposition mayors of Ankara and Istanbul who have both proved remarkably popular in their respective cities and would probably make stronger candidates than Kilicdaroglu. The second largest party in the alliance the right wing nationalist good party, even threatened to leave when it became clear that Kilicdaroglu would be nominated. Although that seems to have been temporarily resolved. You get the idea. Kilicdaroglu is a relatively unpopular candidate who hasn't fared well against Erdogan in the past, and Erdogan will feel confident about beating him again. On to the second reason, the so-called Kurdish question.

Generally, The Kurdish question refers to the fact that the Kurdish people do not have a homeland. But in the context of Turkey, it refers to the tension between Turkey's Kurdish population, especially its more nationalist elements, and the Turkish state, and the question of how to resolve them. The Turkish state has been fighting against Kurdish nationalist movements, most notably the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, since the PKK carried out a series of terrorist attacks on Turkish soil in the mid 80s. In its early years, when Erdogan still wanted to join the EU, his AKP party actually made a real effort to improve relations with Turkey's Kurdish minority and begun unprecedented peace negotiations with the PKK in 2013. But they collapsed two years later after Erdogan's AKP party lost its majority at the June 2015 elections and the AKP declared Kurdish independence in southeastern Turkey. Erdogan then did a complete U-turn, taking up the threat of Kurdish terrorism and massively increasing Turkey's military presence in southeastern Turkey and Syria. This strategy apparently paid dividends, and when he won a healthy majority in the 2018 election, Erdogan himself declared that he had solved the Kurdish question.

However, while it might not be quite as high up on Turkish voters priorities as it once was in the last year or so, Erdogan has suggested that he might revisit the Kurdish question, presumably for political gain. Erdogan's demands for accepting Sweden and Finland into NATO have mostly revolved around withdrawing their support for certain Kurdish groups. And last year, Erdogan announced that he would be sending troops into the semi-autonomous Kurdish region in Syria, known as Rojava. This might be an attempt to remind the electorate that Kurdish separatism is a genuine security threat and paint the opposition bloc who have made moves to woo Turkey's largest Kurdish party, the HDP, as too soft or friendly with the Kurds. Polling suggests that broadly Erdogan's Alliance and the opposition bloc are both on about 45%, with the HDP taking up the remaining 10%, which means if the opposition can sweet talk them into a coalition, they could guarantee themselves a majority.

Kilicdaroglu, for example, has expressed support for the idea of teaching the Kurdish language in state run schools, and four of the six parties in the opposition bloc have met with major Kurdish politicians recently. Basically, the point here is that Erdogan has a track record of instrumentalizing the Kurdish question for political gain, and it looks like he's readying up to do it again. The third reason Erdogan could still win over the electorate is the AKP's control over Turkey's political institutions. Essentially, after 20 years in power, Erdogan and the AKP have significant influence over Turkey's institutional infrastructure, including the media and the judiciary. And he'll use every tool at his disposal to help him win the next election.

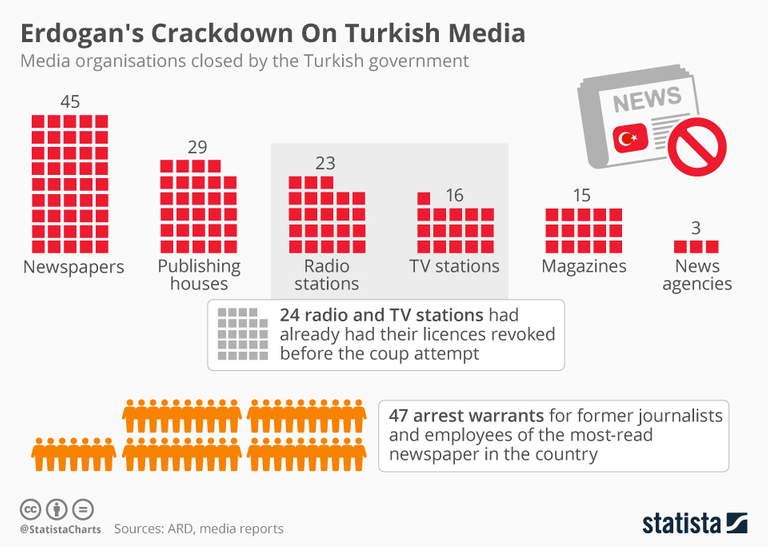

With the media, for example. Erdogan has got into the habit of banning or suspending opposition media outlets and shutting down social media when it suits him. The AKP have also passed a series of anti-democratic laws and packed the judiciary with AKP loyalists, and Turkey's courts have stepped up their attacks on opposition politicians accordingly. In May, for example, the head of the Chp's Istanbul branch was banned from politics for an anti Erdogan tweet. In December, Ekrem Imamoglu was sentenced to almost three years in prison and barred from politics for tweets mocking the judges who cancelled the mayoral election results in 2019. And the HDP looks like it's about to be shut down over its links to Kurdish nationalist groups. You get the idea, while Erdogan might be struggling at the moment, the AKP's control over Turkey's institutions means he can essentially ban unfriendly media coverage or if that doesn't work, just jail all his political opponents.