Fiction: The weight of guilt/ El peso de la culpa (ENG/ ESP)

The weight of guilt

"Return, son, these are your lands and with your help, we will get ahead. You provide the strength, the youth, and I will provide the experience,” his ailing father had told him a thousand times, but Felipe hated it all: too much mountain, too much poverty, too many people.

"What are you going to study what, Felipe? What I need is for you to stay here, realizing all this,” old Eulogio had told him, but Felipe had refused to stay.

"Look, I'm old now, son, and someone has to take care of the ranch,” the old man had insisted, but Felipe, who always believed he was destined for great things, had turned a deaf ear to his father's requests.

Even when resources dwindled, Felipe, enraged, called his father for an explanation:

"I am old now and cannot realize everything, Felipe. There are cattle thieves and the harvest has been lost because of the great summer. What little is done, I send it to you every month,” Eulogio justified himself to his son.

"If what you want is for me to return, I am afraid to inform you that I will not,” said Felipe, poisoned with pride.

But even though his son refused to return, Eulogio continued to help his firstborn:

"His mother would never forgive me. Before she died, she told me to take care of him,” said the poor old man, who in recent years had had to mortgage the farm and borrow money to pay for Felipe's university studies, who despite having spent more than ten years studying, had not yet graduated as a lawyer.

"Typical of these uncultured towns",_ he thought looking with contempt at the walls of that which had been his home.

When he stood in front of the coffin, he looked at his father's face through the thin glass. He shuddered and felt a shiver run down his spine: his father's pale face was full of furrows, wrinkles typical of old age; but it was his eyes that caused Philip to shudder. His eyes were open, dilated, as if in the last moment of his life he had seen someone or something atrocious. That image caused Philip to take his eyes off the urn as if he were afraid that those eyes were chasing him.

"Help load the coffin. That was your father's last wish,” they said and looked at Felipe with hatred and Felipe had no way to refuse.

Then three men took three corners and Felipe stood on one. Between the four of them they lifted the coffin and put it on his shoulders. The sun burned the heads of the procession of people accompanying the dead man. Suddenly Felipe heard someone say:

"He died with his eyes open because he wanted to see the son and the son never came",_ they murmured and Felipe remembered the father's eyes, cold, inert, lifeless. Then, suddenly, Felipe felt an enormous weight on him, as if the father weighed a ton, as if the coffin he was carrying on his shoulders was carrying stones rather than a corpse. Under the weight, Felipe's body began to stoop and his face began to deform with pain. Unable to do anything, Felipe fell to his knees on the ground, bent under the weight. Then he heard the murmur of the people:

"It is the weight of guilt that brought him to his knees",_ and although Felipe tried to get up, he did not succeed.

All images are free of charge and the text is my own, translated in Deepl

Thank you for reading and commenting. Until a future reading, friends

![Click here to read in spanish]

El peso de la culpa

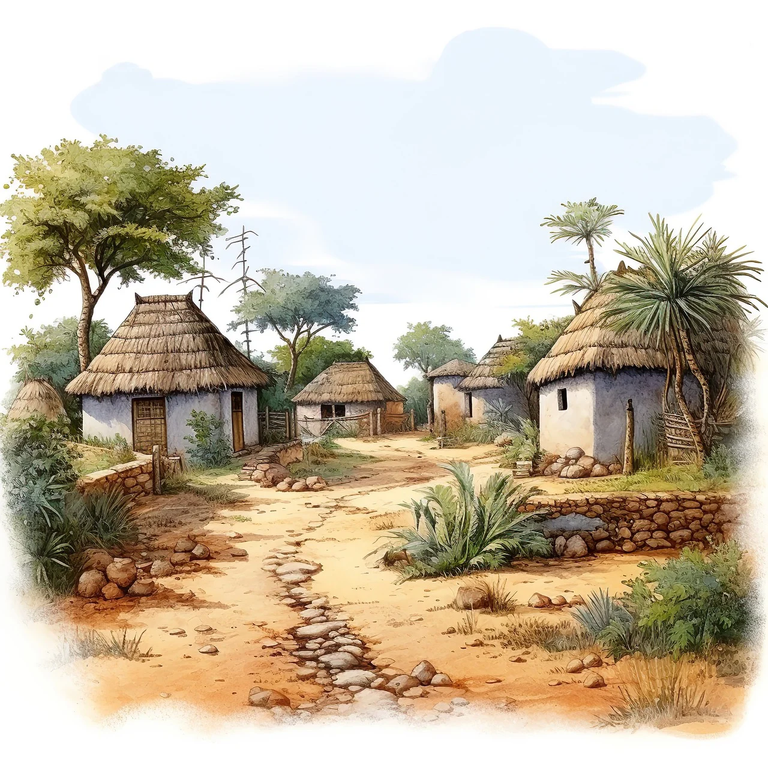

Felipe llegó en la mañana cuando faltaban pocas horas para el entierro. El camino hacia la casa se hizo largo: las calles polvorientas, sin asfaltas, estaba llenas de escombros y agua empozada. Cuando se asomó por la puerta, todos los que estaban reunidos dentro de la casa, voltearon a verlo, como si trajera un sonajero en los pies. Sintió que todos los ojos se posaban sobre él amargamente, en un reclamo silencioso. Hasta los perros famélicos y callejeros llegaron hasta él para ladrarle a su sombra que intentaba permanecer erguida. Mientras caminaba hacia el féretro, con su impecable traje negro, recordó que hacía diez años que se había ido de aquel pueblo y que jamás, después de aquel entonces, aunque su padre, Eulogio, le había rogado, había querido volver:

_Regresa, hijo, estas son tus tierras y con tu ayuda, saldremos adelante. Tú poner la fuerza, la juventud y yo pongo la experiencia –le había repetido una y mil veces su padre enfermo, pero Felipe odiaba todo aquello: demasiado monte, demasiada pobreza, demasiado pueblo.

Después de la muerte de la madre, Felipe se había quedado solo con Eulogio, un hombre campesino, analfabeta, que solo sabía de tierra y ganado, y que veía a su hijo como el futuro sucesor de sus bienes. Pero Felipe, aunque sabía que aquella hacienda era la gallina de los huevos de oro que pagaba todos sus gustos, estaba negado a tomar las riendas de todo aquello y por eso decidió irse a la ciudad a estudiar abogacía:

_¿Qué vas a estudiar qué, Felipe? Yo lo que necesito es que te quedes aquí, dándote cuenta de todo esto –le había dicho el viejo Eulogio, pero Felipe se había negado a quedarse.

_Mira que ya estoy viejo, hijo y alguien se debe dar cuenta de la hacienda –había insistido el anciano, pero Felipe, quien siempre se creyó que estaba destinado para grandes cosas, se había hecho el sordo a las peticiones del padre.

Incluso, cuando mermaron los recursos, Felipe, enfurecido, llamó al padre pidiendo una explicación:

_Ya estoy viejo y no puedo darme cuenta de todo, Felipe. Hay ladrones de ganado y la cosecha se ha perdido a causa del gran verano. Lo poco que se hace, te lo envío cada mes –se justificaba Eulogio ante el hijo.

_Si lo que quiere es que vuelva, temo informarle que no lo haré –afirmaba Felipe envenenado de soberbia.

Pero aunque su hijo se negaba a volver, Eulogio seguía ayudando a su primogénito:

_Su mamá no me lo perdonaría. Antes de morirse me dijo que me diera cuenta de él –decía el pobre viejo, que en los últimos años había tenido que hipotecar la hacienda y pedir prestado para costear la carrera universitaria de Felipe, que a pesar de haber pasado más de diez años estudiando, aún no se había graduado de abogado.

Mientras que Felipe se acercaba al féretro, escuchó que detrás y alrededor de él había miles de cuchicheos que zumbaban en sus oídos como el sonido de mil moscas:

_Típico de estos pueblos incultos –pensó mirando con desprecio las paredes de aquella que había sido su casa.

Cuando estuvo frente al ataúd, miró el rostro de su padre a través del vidrio delgado. Se estremeció y sintió que un escalofrío recorría toda la espina dorsal: el rostro pálido del padre, estaba lleno de surcos, arrugas propias de la vejez; pero eran sus ojos los que provocaban en Felipe un gran estremecimiento. Los ojos estaban abiertos, dilatados, como si en el último momento de vida hubiese visto a alguien o algo atroz. Aquella imagen hizo que Felipe se despegara de la urna como si tuviera miedo de que aquellos ojos lo persiguieran.

Cuando llegó la hora del entierro, los hombres del pueblo le dijeron a Felipe:

_Ayuda a cargar el cajón. Esa fue la última voluntad de tu padre –dijeron y miraron a Felipe con odio y Felipe no tuvo cómo negarse.

Entonces, tres hombres tomaron tres esquinas y Felipe se puso en una. Entre los cuatros alzaron el ataúd y se lo pusieron sobre los hombros. El sol quemaba las cabezas de la procesión de gente que iba acompañando al muerto. De repente Felipe escuchó que alguien decía:

_Murió con los ojos abiertos porque quería ver al hijo y el hijo nunca llegó –murmuraban y Felipe recordó los ojos del padre, fríos, inertes, sin vida. Entonces, de repente, Felipe sintió un peso enorme sobre él, como si el padre pesara una tonelada, como si en el féretro que llevaba sobre los hombros más que un cadáver, llevara piedras. Ante el peso, el cuerpo de Felipe comenzó a encorvarse y su rostro comenzó a deformarse de dolor. Sin poder hacer nada, Felipe cayó arrodillado en la tierra doblegado por el peso. Entonces escuchó el murmullo de la gente:

_Es el peso de la culpa el que lo arrodilló –y aunque Felipe intentó levantarse, no lo logró.

Thank you very much for your appreciation and support, friends. Success

Congratulations @nancybriti1! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 180000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPThank you for the information

That's great @nancybriti1! We're here to encourage you to achieve your next goals on Hive!

BTW, we noticed we miss your support for our proposal. Mays we ask you to check it out and consider supporting it?

All you need to do is to click on the "support" button on this page: https://peakd.com/proposals/248.

Thank you!

Such guilt Felipe will have to live with for a long time in his life.

That is the heaviest of faults! Greetings and thanks for commenting

A very interesting story. A son who will carry the guilt for a long time. While reading your story I remembered many similar cases and it is really very sad that it happens in real life.

Thanks for sharing your story.

Good day.

That's right, my friend. There are many such cases. Sadly. Greetings and thanks for your comment