[ENG-SPN] Parzival

Masterpiece by Wolfram von Eschenbach, whose name, however, is no more than a simple epitaph to a personality that fades, like good legends, at the mercy of the dense fog behind which he gets married, more often than not. we imagine, reality with fiction, 'Parzival', possibly, is the esoteric work with the richest symbolism, of all those that the Middle Ages bequeathed to us, related or not to those fabulous Grail cycles, which are supposed to have been surreptitiously introduced in the West by Cistercians and Templars and that they contain enough pagan elements, both of Eastern and Celtic origin, so that they were not at all to the liking of Holy Mother Church, who rejected them completely, annoyed, of course, by the pronounced whiff of sulfur and heterodoxy developed in each and every one of the scenes and situations starring all those heroes, whose names - Arthur, Lancelot, Galahad, Gawain - now seem so l far away, as are, however, the childhoods of all those who, like Dante, are already halfway through our lives and even a step beyond.

In general terms, the story that Wolfram presents us, under the guise of the life, work and circumstance of Parzival, 'the noblest of all brutes', is none other than that, which, seen through that metaphorical Veil of Isis, which is, on many occasions, Psychology, tells us about the arduous evolution of human consciousness, until it merges, in a willful hyeros-gamos or sacred marriage, with that other part, divine and superhuman, that resides in the most recess of the psyche and to which all the great Masters of Humanity refer, when, in short, they advise that: 'do not look outside, what has always been inside you'.

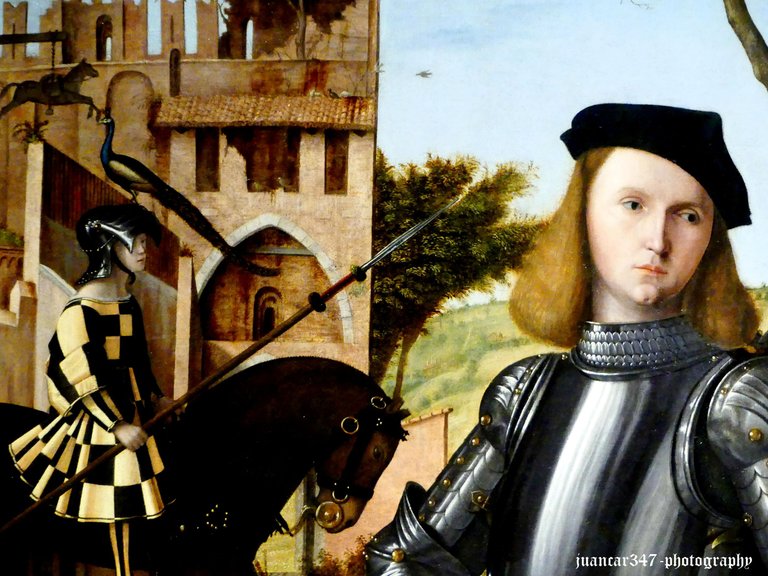

All these ideas, circumstances, arguments or speculations come to mind every time I have the opportunity to contemplate one of the great masterpieces of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, in whose fascinating search, attentive observers are never lacking: 'Young gentleman in a landscape', a work that was always mistakenly attributed to Alberto Dürer, until, in 1958, after a first cleaning, the signature of its true author, Vittore Carpaccio, was discovered, and there were also many speculations collected throughout the story, about the identity of the melancholy knight, who could well be, after all, both the Duke of Urbino, as is currently thought, and the mythical knight of God, the noble Parzival.

Obra magistral de Wolfram von Eschenbach, cuyo nombre, sin embargo, no deja de ser un sencillo epitafio a una personalidad que se diluye, como las buenas leyendas, a merced de las tupidas nieblas tras las que contrae nupcias, en más ocasiones de las que imaginamos, la realidad con la ficción, ‘Parzival’, posiblemente, sea la obra esotérica con más rico simbolismo, de todas cuantas el Medievo nos legó, relacionadas o no con esos fabulosos ciclos del Grial, que se supone, fueron introducidos subrepticiamente en Occidente por cistercienses y templarios y que contienen los suficientes elementos paganos, tanto de origen oriental como céltico, como para que no fuera, en absoluto, del agrado de la Santa Madre Iglesia, que los rechazó por completo, molesta, qué duda cabe, por el pronunciado tufillo a azufre y heterodoxia desarrollados en todas y cada una de las escenas y situaciones protagonizadas por todos aquellos héroes, cuyos nombres -Arturo, Lanzarote, Galahad, Gawain- parecen ahora tan lejanos, como lo son, no obstante, las infancias de todos aquellos que ya, como Dante, nos encontramos a la mitad de nuestra vida e incluso, un paso más allá.

En líneas generales, la historia que Wolfram nos presenta, bajo la apariencia de la vida, obra y circunstancia de Parzival, ‘el más noble de todos los brutos’, no es otra, que aquella, que, vista a través de ese metafórico Velo de Isis, que es, en muchas ocasiones, la Psicología, nos refiere la ardua evolución de la consciencia humana, hasta fundirse, en un voluntarioso hyeros-gamos o matrimonio sagrado, con esa otra parte, divina y sobrehumana, que reside en lo más recóndito de la psique y a la que hacen referencia todos los grandes Maestros de la Humanidad, cuando, en resumidas cuentas, aconsejan aquello de: ‘no busques fuera, lo que siempre ha estado dentro de ti’.

Todas estas ideas, circunstancias, argumentos o especulaciones me vienen a la mente toda vez que tengo ocasión de contemplar una de las grandes obras maestras del Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza de Madrid, en cuya fascinante búsqueda, nunca faltan atentos observadores: ‘Joven caballero en un paisaje’, obra que estuvo siempre equivocadamente atribuida a Alberto Durero, hasta que, en 1958, tras una primera limpieza, se descubrió la firma de su verdadero autor, Vittore Carpaccio, siendo muchas, además, las especulaciones recogidas, a lo largo de la historia, sobre la identidad del melancólico caballero, que bien pudiera ser, después de todo, tanto el duque de Urbino, como se piensa actualmente, como el mítico caballero de Dios, el noble Parzival.

NOTICE: Both the text and the accompanying photographs are my exclusive intellectual property and therefore are subject to my Copyright.

AVISO: Tanto el texto, como las fotografías que lo acompañan, son de mi exclusiva propiedad intelectual y por lo tanto, están sujetos a mis Derechos de Autor.