Réquiem para Franz Kafka (en el centenario de su muerte) (I) (Esp | Eng)

Hace 100 años –3 de junio de 1924– fallecía en un sanatorio de Kierling (Austria), de la complicación pulmonar derivada de su tuberculosis, quien, indiscutiblemente, es uno de los grandes escritores universales: Franz Kafka.

Nació en Praga, que formaba parte de una región denominada Bohemia, entonces perteneciente al imperio austrohúngaro; hoy capital de la República Checa. Era de una familia aristocrática judío-alemana. Es el autor de novelas imprescindibles para un lector de literatura, como La metamorfosis (1915), El proceso (1925) y El castillo (1926), además de un gran número de relatos breves. Como he escrito varios posts sobre él y su obra (ver 1, 2 y 3), y no quiero repetirme, me dedicaré a abordar aspectos relacionados con su muerte, salpicados por parte de su vida amorosa.

Fuente | Source

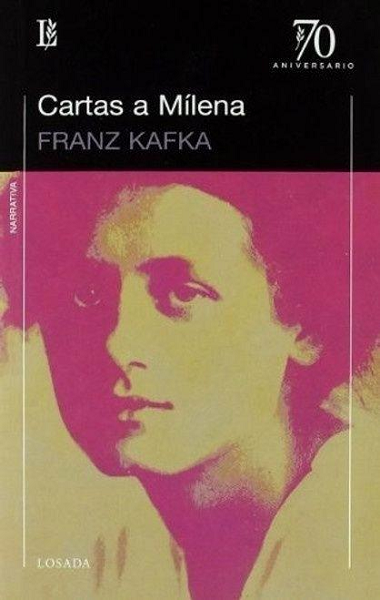

Kafka, de quien se dice que tuvo una vida amorosa truncada o no formalizada en matrimonio, sin embargo, estableció una relación de gran significación con tres mujeres, que pudieran llamarse novias, para usar un término convencional, o amantes en otros: Felice Bauer, Milena Jesenská y Dora Diamant. Con ellas, particularmente con las dos primeras, mantuvo un vínculo epistolar muy abundante, no siempre correspondido; la mayoría de las cartas de Kafka a ellas fueron publicadas póstumamente como libros.

Si bien es un poco difícil para este espacio, intentaré presentar algunos segmentos de esa conexión, sobre todo en lo que se corresponde con una valoración de Kafka, su enfermedad y su muerte. Para ello, en este post me centraré en su relación con Milena, una intelectual checa, casada (aunque con conflictos matrimoniales), que se interesó en traducir a Kafka, quien escribía en alemán. Las cartas a Milena son muy intensas y contradictorias, muchas veces, rasgo propio del escritor. Su correspondencia y puntual encuentro tuvo lugar entre 1920 y 1923.

(...) hasta la verdadera afección pulmonar (media Europa Occidental tiene los pulmones en condiciones más o menos deficientes), que conozco desde hace tres años, me ha traído más bien que mal. Lo mío comenzó hace unos tres años en plena noche, con un vómito de sangre. Me levanté, estimulado, como siempre que nos ocurre algo nuevo (en lugar de permanecer tendido como me indicaron más tarde los médicos), y por supuesto también un poco alarmado, me dirigí a la ventana, me asomé, me encaminé al lavabo, anduve por la habitación, me senté en la cama... Sangre y más sangre. Sin embargo, no me sentía desdichado; porque, poco a poco, por una razón muy precisa, supe que dormiría por primera vez después de tres, casi cuatro años de insomnio, siempre que la hemorragia se detuviera. Y se detuvo (además, desde entonces no se ha vuelto a presentar) y dormí el resto de la noche.

A pesar de todo, escribir hace bien. Me siento más sereno que hace dos horas, mientras estaba con su carta en la silla. Mientras estaba tendido allí, a un paso de mí yacía un escarabajo, patas arriba, desesperado. No podía enderezarse, me habría gustado ayudarlo, era tan fácil hacerlo, bastaba un paso y un empujoncito para brindarle una ayuda efectiva. Pero lo olvidé a causa de la carta. Además no podía ponerme de pie. Por fin, una lagartija logró que volviera a tomar conciencia de la vida que me rodeaba. Su camino la llevó hasta el escarabajo, que ya estaba totalmente inmóvil. De modo que no fue un accidente, me dije, sino una lucha mortal, el raro espectáculo de la muerte natural de un animal. Pero la lagartija al deslizarse por encima del escarabajo, lo enderezó. Por unos instantes continuó inmóvil, como muerto, pero luego trepó la pared como la cosa más natural. Es probable que eso me haya brindado, de alguna manera, un poco de coraje. Lo cierto es que me puse de pie, bebí leche y le escribí a usted.

No quisiera convertirme en un irrespetuoso transgresor de textos tan estrictamente personales, donde se puede percibir la aguda sensibilidad de Kafka, en la que se muestra una conciencia de su inevitable enfermedad, y, a la vez, la expresión de alguna esperanza frente a ella, al menos, para sobrellevarla.

Cerraré esta parte con fragmentos del obituario que escribiera Milena a petición de un diario checo, texto aparecido el 6 de junio de 1924, pero publicado en alemán en 1962.

Anteayer murió en el sanatorio de Kierling en Klosterneuburg, a las afuera de Viena, el doctor Franz Kafka, escritor alemán que vivía en Praga. Pocos aquí le conocían, porque era un ermitaño, un sabio que temía la vida. Durante años padeció una enfermedad de los pulmones, y aunque recibió tratamiento, también la alentó a conciencia y la nutrió espiritualmente. “Cuando el alma y el corazón no pueden soportar la carga, entonces el pulmón se ocupa de la mitad para que al menos el peso quede repartido en parte”, escribió en cierta ocasión en una carta, y así ocurrió con su enfermedad. Ésta le dio una sensibilidad que rayaba lo maravilloso y una claridad mental casi aterradoramente rigurosa; y, por otro lado, este hombre depositó sobre su enfermedad todo el peso de su angustia espiritual. Era tímido, angustiado, sereno y bueno, pero escribió libros terribles y dolorosos. Veía el mundo poblado de demonios invisibles que aniquilaban a las personas indefensas. Era demasiado clarividente, demasiado sabio para vivir, y demasiado débil para luchar, pero su debilidad era la de las almas nobles y bellas que evitan luchar contra el miedo, los malentendidos, el desamor y la mentira intelectual porque saben de antemano que son impotentes y se someten a la derrota para avergonzar a los vencedores.

La esquela de duelo escrita por Milena (puede leerla completa en la referencia dada al final) es muestra indudable de un testimonio afectivo y una comprensión profunda de la personalidad y talante del escritor que fue Franz Kafka que nos conmueve.

Seguiré en un post mañana para contribuir a este homenaje que hacemos a este grande del espíritu moderno.

Referencias | References:

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Kafka

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Kafka

https://web.seducoahuila.gob.mx/biblioweb/upload/Kafka,%20Franz%20-%20Cartas%20a%20Milena.pdf

https://misiglo.es/2021/07/15/el-obituario-de-kafka/

![Click here to read in english]

Requiem for Franz Kafka (on the centenary of his death) (I)

100 years ago – June 3, 1924 – he died in a sanatorium in Kierling (Austria), from pulmonary complications resulting from his tuberculosis, who, indisputably, is one of the great universal writers: Franz Kafka.

He was born in Prague, which was part of a region called Bohemia, then belonging to the Austro-Hungarian empire; today the capital of the Czech Republic. He was from an aristocratic German-Jewish family. He is the author of essential novels for a literature reader, such as The Metamorphosis (1915), The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926 ), as well as a large number of short stories. As I have written several posts about him and his work (see 1, [2](https: //peakd.com/hive-199275/@josemalavem/microficcion-para-franz-kafka-or-microfiction-for-franz-kafka) and [3](https://peakd.com/hive-179291/@josemalavem /kafka-the-trapeze-artist)), and I do not want to repeat myself, I will dedicate myself to addressing aspects related to his death, sprinkled with part of his love life.

Kafka, who is said to have had a love life cut short or not formalized in marriage, nevertheless established a relationship of great significance with three women, who could be called girlfriends, to use a conventional term, or lovers in others: Felice Bauer , Milena Jesenská and [Dora Diamant](https:// es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Diamant). With them, particularly with the first two, he maintained a very abundant epistolary relationship, not always reciprocated; most of Kafka's letters to them were published posthumously as books.

Although it is a bit difficult for this space, I will try to present some segments of that connection, especially as it corresponds to an assessment of Kafka, his illness, and his death. To do this, in this post I will focus on his relationship with Milena, a Czech intellectual, married (although with marital conflicts), who became interested in translating Kafka, who wrote in German. The letters to Milena are very intense and contradictory, many times, a characteristic of the writer. Their correspondence and punctual meeting took place between 1920 and 1923.

(...) even the real lung condition (half of Western Europe has lungs in more or less poor condition), which I have known for three years, has brought me more good than harm. Mine started about three years ago in the middle of the night, with vomiting blood. I got up, stimulated, as always when something new happens to us (instead of lying down as the doctors later told me to do), and of course also a little alarmed, I went to the window, looked out, went to the bathroom, walked around the room, I sat on the bed... Blood and more blood. However, I did not feel unhappy; because, little by little, for a very precise reason, I knew that I would sleep for the first time after three, almost four years of insomnia, as long as the bleeding stopped. And it stopped (plus it hasn't come back since) and I slept the rest of the night.

Despite everything, writing is good. I feel more serene than two hours ago, while I was with her letter on the chair. As I lay there, a beetle lay a step away from me, upside down, desperate. He couldn't straighten himself up, I would have liked to help him, it was so easy to do it, just one step and a little push were enough to give him effective help. But I forgot because of the letter. Plus I couldn't stand up. Finally, a lizard managed to make me aware of the life around me again. Her path took her to the beetle, which was now completely still. So it was not an accident, I told myself, but a deadly struggle, the rare spectacle of the natural death of an animal. But the lizard, sliding over the beetle, righted it. For a few moments he remained motionless, as if dead, but then he climbed the wall as the most natural thing. That probably gave me some courage in some way. The truth is that I stood up, drank milk and wrote to you.

I would not want to become a disrespectful transgressor of such strictly personal texts, where one can perceive Kafka's acute sensitivity, in which an awareness of his inevitable illness is shown, and, at the same time, the expression of some hope in the face of it, at least, to cope with it.

I will close this part with fragments of the obituary that Milena wrote at the request of a Czech newspaper, a text that appeared on June 6, 1924, but published in German in 1962.

The day before yesterday, Dr. Franz Kafka, a German writer who lived in Prague, died in the Kierling sanatorium in Klosterneuburg, outside Vienna. Few here knew him, because he was a hermit, a wise man who feared life. For years she suffered from a lung disease, and although she received treatment, he also thoroughly encouraged her and nourished her spiritually. “When the soul and the heart cannot bear the load, then the lung takes care of half so that at least the weight is distributed in part,” she once wrote in a letter, and this is what happened with her illness. . This gave him a sensitivity that bordered on the marvelous and an almost frighteningly rigorous mental clarity; and, on the other hand, this man placed the full weight of his spiritual anguish on his illness. He was shy, anguished, serene and good, but he wrote terrible and painful books. He saw the world populated by invisible demons that annihilated defenseless people. He was too clairvoyant, too wise to live, and too weak to fight, but his weakness was that of noble and beautiful souls who avoid fighting against fear, misunderstanding, heartbreak and intellectual lies because they know in advance that they are powerless and They submit to defeat to shame the victors.

The mourning note written by Milena (you can read it in full in the reference given at the end) is an undoubted example of an emotional testimony and a deep understanding of the personality and disposition of the writer who was Franz Kafka that moves us.

I will continue in a post tomorrow to contribute to this tribute that we pay to this great of the modern spirit.

Esta publicación ha recibido el voto de Literatos, la comunidad de literatura en español en Hive y ha sido compartido en el blog de nuestra cuenta.

¿Quieres contribuir a engrandecer este proyecto? ¡Haz clic aquí y entérate cómo!

excelente historia, me atrapo, en muy pocas letras has podido describir un pedacito del alma de Kafka

Hola, amigo. Gracias por su visita. En realidad no escribí una historia, sólo reproduje fragmentos de dos cartas de Kafka y parte del obituario de quien fuera una de sus amadas mujeres. Saludos, @profedgar.