Franz Kafka a través de Dora Diamant (en el centenario de su muerte) (y II) (Esp | Eng)

Ayer, fecha del centenario de la muerte del gran escritor universal Franz Kafka, le dediqué un primer post (ver aquí), en el que abordaba parte de su personalidad, enfermedad y muerte, por medio de fragmentos de cartas a una de sus amadas mujeres: Milena Jesenská y del obituario escrito por esta. Este segundo y último post lo enfocaré a valorar el mismo asunto, pero desde la perspectiva de la que fuera su tercera mujer, con la que sí mantuvo una relación casi matrimonial: Dora Diamant.

La figura de Dora Diamant fue todo una enigma hasta hace pocos años; fue gracias a una investigadora estadounidense, curiosamente del mismo apellido: Kathi Diamant, quien, producto de su dedicada averiguación con entrevistas y en periódicos, logró publicar en 2005 el libro Dora Diamant: el último amor de Franz Kafka.

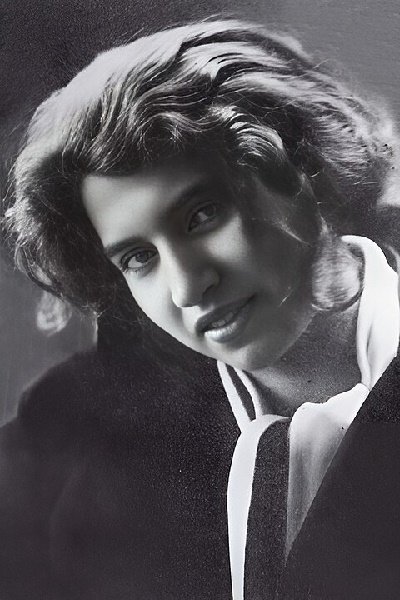

Dora Diamant había nacido en Polonia en 1898, en una familia judía ortodoxa o jasídica. Abandonó la casa, cuando se le quiso casar con un hombre escogido por su padre y emigró a Alemania. Allí estudió teatro, oficio al que se dedicaría luego, llegando a ser una actriz conocida.

Estando en Berlín, participó en varias actividades de la comunidad judía; entre ellas, colaboró como voluntaria en un campamento para niños de Europa del Este, refugiados de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Eso ocurrió en 1923, en el balneario de Müritz, donde ella trabajaba como ayudante de cocina. Allí Dora vio por primera vez a Franz Kafka, quien la atrajo. Pasado un tiempo se unirían como pareja en Berlín; ella tenía 20 años y él 40. Pasaron juntos unos 11 meses y acompañó al escritor hasta el último día de su vida, en el sanatorio de Viena, donde este moriría el 3 de junio de 1924. Los biógrafos del escritor señalan que este se sintió a gusto con Dora: “ella no le exigió nada excepto su mera existencia y él se sintió libre con ella”.

Fue una defensora de la cultura judía, en la que educó, en gran medida, a Kafka, quien sentía atracción por el judaísmo (en su ascendencia familiar ya estaba esa herencia). Luego de la muerte de Kafka, Dora casi desapareció de la mira, pero se logró conocer que sufrió duros momentos de persecución por el régimen nazi, pero también por el comunismo soviético. Murió a los 54 años en 1952.

de Georg Maas y Judith Kaufmann

Fuente | Source

En un libro organizado por el editor Hans-Gerd Koch, publicado en 2009, bajo el título Cuando Kafka vino hacia mí, se incluyeron, entre los testimonios de parientes, amigos y conocidos de Kafka, las notas escritas por Dora Diamant, registradas como “Mi vida con Franz Kafka”. Reproduciré a continuación algunos fragmentos admirables de dichas notas.

Un día anunciaron en el centro que el doctor Franz Kafka iba a venir a cenar. Yo en aquel momento tenía mucho que hacer en la cocina. Cuando levanté la vista de mi trabajo—la habitación se había oscurecido, alguien estaba allí fuera delante de la ventana— reconocí al caballero de la playa. Entonces entró. No sabía que se trataba de Kafka y que la mujer con quien le había visto en la playa era su hermana. Con voz suave dijo: «¡Unas manos tan delicadas y tiene usted que hacer un trabajo tan cruento!» (Kafka por entonces era vegetariano).

Lo más llamativo en su rostro eran los ojos, que mantenía abiertos, a veces incluso muy abiertos, tanto si estaba hablando como si escuchaba. No miraban asustados, como se ha afirmado alguna vez de él. Más bien había en ellos una expresión de asombro. Tenía los ojos marrones, tímidos, y resplandecían cuando hablaba. En ellos aparecía de vez en cuando una chispa de humor, que sin embargo era menos irónica que pícara, como si supiera cosas que las demás personas desconocían. Pero carecía por completo de sentido de la solemnidad.

Kafka sufría mucho por las condiciones de vida externas, aunque consigo mismo procedía con mucho rigor. En su opinión, no tenía ningún derecho a desentenderse de lo que ocurría a su alrededor. Para él, el camino hasta la ciudad suponía siempre una especie de subida al Gólgota, un esfuerzo que casi lo aniquilaba.

Kafka tenía que escribir porque la escritura era el aire que necesitaba para vivir. Lo respiraba los días en los que escribía. Cuando se dice que estuvo escribiendo durante catorce días, significa que no paró de hacerlo durante catorce días y catorce noches. Por lo general, antes de empezar, deambulaba torpe y descontento por la casa. Entonces hablaba poco, comía sin apetito, no se interesaba por nada y se mostraba muy abatido. Quería estar solo. Al principio, yo no entendía aquellos estados de ánimo. Más tarde aprendí a notar siempre cuándo empezaba a escribir. Por lo general mostraba el más vivo interés incluso por las cosas más insignificantes, pero en días como ésos su atención se desvanecía por completo.

La literatura era para él algo sagrado, absoluto, intangible, puro y grande. Bajo el término literatura Kafka no entendía la que se escribe para el momento. Como no estaba seguro de la mayoría de las cosas de la vida, se expresaba con mucha prudencia. Sin embargo, cuando se trataba de literatura no transigía y no estaba dispuesto a aceptar ningún compromiso, pues toda su existencia se veía afectada por ella. No sólo quería ir al fondo de las cosas... Él mismo estaba en el fondo. Tratándose de la solución de los extravíos humanos, no quería conformarse con medianías. Había experimentado la vida como un laberinto en el que no podía ver ninguna salida.

Lo inquietante en la enfermedad mortal de Kafka fue su brusca aparición. Me di cuenta de que fue él quien la obligó a mostrarse. Para él fue una especie de liberación. Le habían quitado el poder de decisión de las manos. Kafka saludó a la enfermedad sin más ni más, aun cuando en el último momento de su vida le hubiera gustado seguir viviendo.

Años después he leído a menudo los libros de Kafka, siempre con el recuerdo de cómo me los leía él mismo en voz alta. (...) En él hay una conciencia inveterada, viejos asuntos y un viejo temor. Su mente conocía matices más finos que los que en general puede concebir la mentalidad moderna. No es el representante de una época, como tampoco de un pueblo y su destino. Del mismo modo que su realismo no reproduce la vida de todos los días, su lógica es absoluta, comprimida, y en ella sólo se puede vivir durante unos breves instantes.

No resistí la provocación de reproducir un número amplio de fragmentos de las memorias de Dora Diamant, que hablan por sí mismos. Así como no puedo resistir la posibilidad de compartir con ustedes uno de los momentos más hermosos del texto de Dora, con el cual me despido en este homenaje a Kafka y también a Dora Diamant.

Las cartas de una muñeca

Cuando vivíamos en Berlín, Kafka iba con frecuencia al parque de Steglitz. Yo le acompañaba a veces. Un día nos encontramos a una niña pequeña que lloraba y parecía totalmente desesperada. Hablamos con ella. Franz le preguntó qué era lo que la apenaba, y nos enteramos de que había perdido su muñeca. Enseguida inventa él una historia con la que explicar aquella desaparición. «Tu muñeca tan sólo está haciendo un viaje. Lo sé. Me ha enviado una carta». La niña desconfió un poco: «¿La has traído?». «No, la he dejado en casa, pero mañana te la traeré». La niña, ahora curiosa, ya había olvidado en parte su pena. Y Franz volvió enseguida a casa para escribir la carta.Se puso manos a la obra con toda seriedad, como si se tratara de escribir una obra. Estaba en el mismo estado de tensión en el que se encontraba siempre en cuanto se sentaba al escritorio, aunque sólo fuera para escribir una carta o una postal. Por lo demás era un verdadero trabajo, tan esencial como los otros, porque había que preservar a la niña de la decepción costara lo que costase, y había que contentarla de verdad. La mentira debía, por tanto, convertirse en verdad a través de la verdad de la ficción. Al día siguiente llevó la carta a la pequeña, que le estaba esperando en el parque. Como la pequeña no sabía leer, él lo hizo en voz alta. La muñeca le explicaba en la carta que estaba harta de vivir siempre en la misma familia, y expresaba su deseo de experimentar un cambio de aires, en una palabra, quería separarse por algún tiempo de la niña, a la que quería mucho. Prometía escribir todos los días. Y Kafka, de hecho, escribió una carta diaria en la que siempre informaba de nuevas aventuras, que se desarrollaban muy deprisa, de acuerdo con el ritmo de vida especial de las muñecas. Al cabo de unos días, la niña había olvidado la verdadera pérdida de su juguete y ya sólo pensaba en la ficción que se le había ofrecido como sustituto. Franz ponía en cada frase de la historia tanto detalle y sentido del humor, que el estado en que se encontraba la muñeca resultaba del todo comprensible: la muñeca había crecido, había ido al colegio, había conocido a otras gentes. Aseguraba una y otra vez que quería a la niña, pero aludía a las complicaciones que iban surgiendo, a otras obligaciones y otros intereses que de momento no le permitían retomar la vida en común. A la niña se le pidió que reflexionara, y así se la preparó para la inevitable renuncia.

El juego duró por lo menos tres semanas. Franz tenía un miedo terrible ante la idea de cómo darle fin, pues aquel final debía ser un verdadero final, es decir, debía hacer posible el orden que reemplazara el desorden provocado por la pérdida del juguete. Pensó largamente y al final se decidió por hacer que la muñeca se casara. Primero describió al joven marido, la fiesta de compromiso, los preparativos de boda. Después, con todo detalle, la casa de los recién casados: «Tú misma comprenderás que en el futuro tendremos que renunciar a volver a vernos». Franz había resuelto el pequeño conflicto de la niña a través del arte, gracias al medio más efectivo del que él personalmente disponía para ordenar el mundo.

![Click here to read in english]

Franz Kafka through Dora Diamant (on the centenary of her death) (and II) (Esp | Eng)

Yesterday, the centenary of the death of the great universal writer Franz Kafka, I dedicated a first post to him (see here), which addressed part of his personality, illness and death through fragments of letters to one of his beloved women : Milena Jesenská and the obituary written by her. This second and last post I will focus on evaluating the same issue but from the perspective of his third wife, with whom he had an almost marital relationship: Dora Diamant.

The figure of Dora Diamant was quite an enigma until a few years ago; It was thanks to an American researcher, curiously with the same last name: Kathi Diamant, who, as a result of her dedicated research with interviews and newspapers, managed to publish the book in 2005: Dora Diamant: the last love of Franz Kafka.

Dora Diamant was born in Poland in 1898, into an Orthodox or Hasidic Jewish family. She left home when she wanted to marry a man chosen by her father and emigrated to Germany. There she studied theater, a profession to which she would later dedicate herself, becoming a well-known actress.

While in Berlin, she participated in various Jewish community activities; Among them, she collaborated as a volunteer in a camp for children from Eastern Europe, refugees from the First World War. That happened in 1923, in the Müritz spa, where she worked as a kitchen assistant. There Dora saw Franz Kafka for the first time, who attracted her. After a while they would join as a couple in Berlin; She was 20 years old and he was 40. They spent about 11 months together and she accompanied the writer until the last day of his life, in the Vienna sanatorium, where he would die on June 3, 1924. The writer's biographers point out that with Dora Kafka He felt at ease: “she did not demand anything from him except her mere existence and he felt free with her.”

She was a defender of Jewish culture, in which she largely educated Kafka, who was attracted to Judaism (that heritage was already present in her family ancestry). After Kafka's death, Dora almost disappeared from the spotlight, but it was learned that she suffered harsh moments of persecution by the Nazi regime, but also by Soviet communism. She died at age 54 in 1952.

In a book organized by the editor Hans-Gerd Koch, published in 2009, under the title When Kafka came to me, the notes written by Kafka were included among the testimonies of relatives, friends and acquaintances of Kafka. Dora Diamant, registered as “My life with Franz Kafka”. I will reproduce below some admirable fragments of these notes.

One day they announced at the center that Dr. Franz Kafka was coming to dinner. At that time I had a lot to do in the kitchen. When I looked up from my work—the room had darkened, someone was standing outside the window—I recognized the gentleman from the beach. Then he entered. He didn't know that it was Kafka and that the woman he had seen him with on the beach was his sister. In a soft voice he said: "Such delicate hands and you have to do such bloody work!" (Kafka was a vegetarian at the time).

The most striking thing about his face were his eyes, which he kept open, sometimes even wide open, whether he was talking or listening. They did not look scared, as has sometimes been said about him. Rather, there was an expression of astonishment on them. He had shy brown eyes, and they shone when he spoke. From time to time a spark of humor appeared in them, which however was less ironic than mischievous, as if she knew things that other people did not know. But she had no sense of solemnity at all.

Kafka suffered a lot from the external living conditions, although he treated himself very rigorously. In his opinion, he had no right to ignore what was happening around him. For him, the way to the city always involved a kind of climb to Golgotha, an effort that almost annihilated him.

Kafka had to write because writing was the air he needed to live. He breathed it on the days he wrote. When it is said that he was writing for fourteen days, it means that he did not stop writing for fourteen days and fourteen nights. Usually, before starting, he would wander around the house clumsily and discontentedly. Then he spoke little, ate without appetite, was not interested in anything and seemed very dejected. He wanted to be alone. At first, I didn't understand those moods. Later I learned to always notice when he started writing. By He usually showed the keenest interest in even the most insignificant things, but on days like these his attention completely faded.

Literature was for him something sacred, absolute, intangible, pure and great. By the term literature Kafka did not understand what was being written at the time. Since he was not sure about most things in life, he expressed himself very cautiously. However, when it came to literature he did not compromise and he was not willing to accept any compromise, because his entire existence was affected by it. He not only wanted to get to the bottom of things...He was at the bottom himself. When it came to the solution of human errors, he did not want to settle for mediocrities. He had experienced life as a maze in which he could see no way out.

The disturbing thing about Kafka's mortal illness was his sudden appearance. I realized that he was the one who forced her to show herself. For him it was a kind of liberation. They had taken the power of decision out of his hands. Kafka greeted the illness without further ado, even though at the last moment of his life he would have liked to continue living.

Years later I have often read Kafka's books, always with the memory of how he read them aloud to me himself. (...) In him there is an inveterate conscience, old issues and an old fear. His mind knew finer nuances than the modern mentality can generally conceive. He is not the representative of an era, nor of a people and their destiny. In the same way that his realism does not reproduce everyday life, his logic is absolute, compressed, and can only be lived in for a few brief moments.

I could not resist the provocation of reproducing a large number of fragments from Dora Diamant's memoirs, which speak for themselves. Just as I cannot resist the possibility of sharing with you one of the most beautiful moments of Dora's text, with which I say goodbye in this tribute to Kafka and Dora Diamant.

The letters of a doll

When we lived in Berlin, Kafka frequently went to Steglitz Park. I accompanied him sometimes. One day we met a little girl who was crying and seemed totally desperate. We talk to her. Franz asked her what was distressing her, and we learned that she had lost her doll. He immediately invents a story to explain that disappearance. «Your doll is just taking a trip. I know. She sent me a letter. The girl was a little suspicious: "Did you bring her?" "No, I left it at home, but tomorrow I will bring it to you." The girl, now curious, had already partly forgotten her grief. And Franz immediately returned home to write the letter.

He set to work with all seriousness, as if he were writing a work. He was in the same state of tension that he always found himself in as soon as he sat down at his desk, even if it was just to write a letter or a postcard. For the rest, it was a real job, as essential as the others, because the girl had to be protected from her disappointment at any cost, and she had to be truly happy. The lie had, therefore, to become truth through the truth of fiction. The next day he took the letter to the little girl, who was waiting for him in the park. Since the little girl didn't know how to read, he did it out loud. The doll explained in the letter that she was tired of always living in the same family, and she expressed her desire to experience a change of scenery, in a word, she wanted to separate for some time from the girl, whom she loved. a lot. He promised to write every day. And Kafka, in fact, wrote a daily letter in which he always reported on new adventures, which developed very quickly, in accordance with the special rhythm of life of the dolls. After a few days, the girl had forgotten the real loss of her toy and she only thought about the fiction that she had offered herself as a substitute for her. Franz put so much detail and sense of humor into each sentence of the story that the state of the doll was completely understandable: the doll had grown up, she had gone to school, she had met other people. He assured time and time again that he loved the girl, but alluded to the complications that were arising, to other obligations and other interests that at the moment did not allow them to resume their life together. The girl was asked to reflect, and so he prepared her for her inevitable resignation.

The game lasted at least three weeks. Franz was terribly afraid of the idea of how to end it, because that ending had to be a true ending, that is, it had to make possible the order that would replace the disorder caused by the loss of the toy. He thought long and hard and finally decided to get the doll married. He first described the young husband, the engagement party, the preparations wedding Then, in detail, the house of the newlyweds: "You yourself will understand that in the future we will have to give up seeing each other again." Franz had resolved the girl's little conflict through art, thanks to the most effective means that he personally had at his disposal to order the world.

Referencias | References:

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Diamant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Diamant

https://www.acantilado.es/wp-content/uploads/Extracto_Kafka.pdf

https://www.revistaadynata.com/post/kafka-cartas-de-una-mu%C3%B1eca---dora-diamant

https://www.lanacion.com.ar/el-mundo/vivir-con-franz-un-solo-dia-valia-mas-que-toda-su-obra-dora-diamant-la-mujer-en-cuyos-brazos-murio-nid02062024/

Congratulations @josemalavem! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 2400 posts.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

Thanks, @hivebuzz.

That's great @josemalavem! We're here to encourage you to achieve your next goals on Hive!

Esta publicación ha recibido el voto de Literatos, la comunidad de literatura en español en Hive y ha sido compartido en el blog de nuestra cuenta.

¿Quieres contribuir a engrandecer este proyecto? ¡Haz clic aquí y entérate cómo!